It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future. – Yogi Berra (?[1])

The confluence of three events this past week shapes this post:

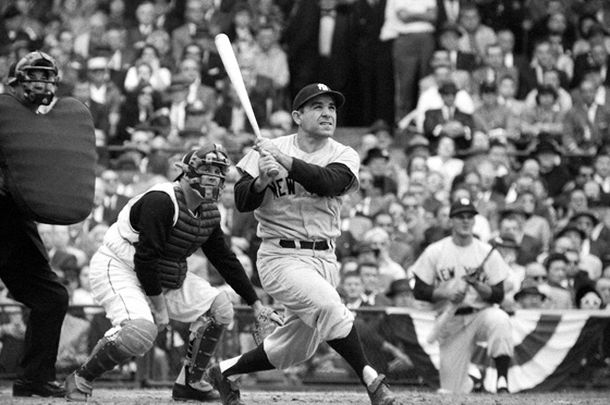

At age 90, former New York Yankee catcher Yogi Berra passes. My generation knew him as one of the great catchers of all time. Growing up, I got to see him play a couple of times in the old Yankees stadium (as in, the original stadium built in 1923 before its 1970’s renovation, and its eventual replacement by today’s Yankee Stadium in 2009). Back then, the pillars of the old structure and the fedoras and the haze of cigarette smoke from the adults obscured my view of the field but didn’t diminish the excitement of seeing Yogi, and Mickey Mantle, Phil Rizzuto, Whitey Ford, Allie Reynolds and other legends actually play the game).

Today’s generation, at least those who don’t confuse him with Yogi Bear, remembers Mr. Berra more for his malapropisms and mis-pronouncements, many captured in spirit in his classic, The Yogi Book: I Really Didn’t Say Everything I Said! One of those quotes frequently cited is the lead-in reflection above, on predictions.

That quote holds particular salience for meteorologists, and well it should. More than one writer (Nate Silver and David Orrell come to mind) have suggested that meteorologists are better at predictions than most – including, for example, economists, election pollsters, and sports prognosticators – and perhaps even the oracle at Delphi. Meteorologists are right to take pride and satisfaction in harnessing science and technology to the task of protecting lives and property in the face of weather hazards.

Meteorologists are also right to recognize that improved predictive skill is urgently needed. Here’s an analogy: Imagine that you’ve been driving a car for several daylight hours on the interstate highways of the high plains of Nebraska and Colorado. You can see miles ahead in the bright sunlight, and the road seems to stretch on straight and true, without limit. But night falls as you reach and enter the Rockies. Suddenly, just as visibility is limited to that provided by the headlights, a dense fog rolls in and the road ahead becomes a succession of twists and curves. It hits you: you’re driving too fast for conditions.

In microcosm, that’s the predicament of the human race. For all of history, our numbers have been limited and our weather-, water-, and climate-related decisions could be based on persistence. We could usefully assume that conditions we’d face in the future with regard to extremes of flood and drought, storm and calm would be similar to those we’d faced in the recent past. Today – whether we’re trying to provide for public safety in the face of weather extremes; or keeping surface and air traffic moving in rain, snow, and ice; or meet food production goals from the coming growing season in light of growing global demands; or storing water to protect us from flood or sustain us through a drought – we’re essentially driving blind. We’re making weather-sensitive decisions based on hope and guess rather than knowledge. We have to start evacuating cities before we know to a certainty that the hurricane will actually hit. We have to decide what crops to plant before we can be sure the coming season will be wet or dry. We are making huge investments in coastal critical infrastructure in the face of indeterminate sea-level rise. The time horizons of these and other decisions greatly exceed the extent of our predictive capability.

Here is where the analogy breaks down. An individual driving too fast for conditions can and does slow the vehicle speed, either in response to the external realities or in response to the pleas and demands of concerned passengers in the car. That’s not what’s happening when it comes to the human race and weather-, water-, and climate-related decisions and actions. Simply “slowing down” the seven-billion-person “vehicle” is not a viable societal option. Crops need to be planted on a rough timetable. Critical coastal infrastructure – the roadways, the waterworks, the electrical grid, and more – needs to be constructed and maintained at a pace dictated by social and technological necessity – even if we can’t yet discern what future natural extremes will stress the system.

For a society that can’t “slow down,”, the alternative of intensifying the headlights, or supplementing them with radar and collision-avoidance gear and GPS thus looks attractive and relatively cost-effective; hence the keen interest in extending the time horizon and improving the specificity of weather, water, and climate prediction, and quickly integrating any new progress into improved decision support tools.

Which brings us to the second event of the past week…

____________________________________________

“Your own responsibility as members of Congress is to enable this country, by your legislative activity, to grow as a nation. You are the face of its people, their representatives. You are called to defend and preserve the dignity of your fellow citizens in the tireless and demanding pursuit of the common good, for this is the chief aim of all politics. A political society endures when it seeks, as a vocation, to satisfy common needs by stimulating the growth of all its members, especially those in situations of greater vulnerability or risk. Legislative activity is always based on care for the people. To this you have been invited, called and convened by those who elected you.” – Pope Francis, speaking to the U.S. Congress

Pope Francis visits the United States. Here in Washington, D.C., prior to the pope’s visit, the news focus was on the likely impact of his schedule on the DC-area commute and the availability of papal-bobblehead dolls. But during his visit, the news coverage morphed into something deeper. The video and audio revealed not a celebrity but a simple man, someone like the rest of us – in this case, a former-barroom-bouncer-turned-parish-priest, an immigrant. And this was not a man needing – hungering – to feed on the adulation of the crowds and the dignitaries. Instead, throughout, he had something to offer: food-for-thought to the great personages, and true material food and blessing to the homeless, the sick, the children, those in prison, young and old alike – all on an individual basis. Whatever his company or circumstances, he was happy, at peace.

And he gave us the greatest gift of all: he reminded us that our individual lives have profound meaning. In fact, here is what he said at the beginning of his address to the Congress, leading in to the quote above: “Each son or daughter of a given country has a mission, a personal and social responsibility.”

Each of us. A personal and social responsibility.

Though the pope used the phrase “social responsibility” here, what he was really saying in words and actions here and throughout his visit was that our lives and work are a sacred calling. Though he didn’t mention meteorologists by name, he included us in remarks both to the Congress and to world leaders at the United Nations. For example, when it came to climate change, he didn’t frame the issue as a mere technological or even a social challenge, but as a spiritual one – a matter of providing simple justice for those poor and weak and otherwise disenfranchised who will bear the brunt of the problem and who are in no position to make their voices heard.

Meteorologists have made great strides over the past several years in recognizing the opportunity to combine forces with social scientists to improve risk communication. But social science tells us that when meteorologists speak of protection of life and property in the abstract, and in relation to large numbers of people versus individuals, we risk falling prey to so-called “psychic numbing.”[2] By contrast, whether addressing climate change, or poverty, or war, or the sexual predation of (a minority of) prelates, or (in a positive vein), the importance of families, the pope found language to articulate the issue, again and again, in terms of the sacred value of the individual.

Which brings us to the third event of the week…

____________________________________________

Hundreds die in Hajj stampede. Talk about psychic numbing. This terrible tragedy – the loss of 770 lives and injured numbering countless more – was not the worst in the history of the hajj but only the worst in the past quarter-century. In 1990 over 1400 pilgrims lost their lives in a similar episode. It is in the nature of these events that sectarian feelings run high and accusations fill the air. Iranian leaders are calling for investigations; some 130 0f the 770 victims were from Iran.

Why mention this here?

Because, in many respects, “evacuation in the face of weather threats” is “stampede” by another name. The 2005 evacuation of Houston under threat of Hurricane Rita and the mobilization of Oklahomans in the face of the El Reno tornado come to mind. In the case of Hurricane Rita, we’re told that in chaotic road conditions some 100 people (many probably with pre-existing health conditions) died from the traffic gridlock and excessive heat prior to hurricane landfall, including 23 elderly who were killed when the bus that had been evacuating them from their nursing home caught fire. The El Reno tornado event saw thousands of people leaving their homes and took to the roads in an ill-advised effort to avoid harm. Some estimates suggest that hundreds of lives might have been lost had the tornado maintained its form and transited the clogged freeways.

If meteorologists have a sacred responsibility for the protection of lives and property, then we have a similar responsibility for encouraging leaders and the public at local, state, and national levels to do everything in their power to reduce the need for evacuation in the face of weather hazards, versus merely to attempt to manage evacuations of ever-increasing scale and complexity. In evacuations of hundreds or even thousands, deaths will be rare. But in emergency responses mobilizing hundreds of thousands or millions, fatalities are inevitable. We need to be strong advocates for better land use and building codes, and increased priority to uninterruptible critical infrastructure.

Our colleagues the dentists know this. Their offices feature happy-tooth signs over the caption “you don’t have to floss all your teeth; just the ones you want to keep.” We need to say something similar: “you don’t have to evacuate all your homes; just the ones you don’t build to code and situate on the floodplain.”

NOAA’s Weather-Ready-Nation initiative and similar programs offer many opportunities to proclaim such a message and build upon it.

In closing, perhaps it’s worthwhile to return to the idea of the sacred value of the individual. I don’t know each and every person who clicks on this blog, or bothers to read each post through. But I do know some of you. And every single one of you already sees your work as a calling, already sees your family, and those who follow your research or use your forecasts or sit in your classes or discuss these matters with you across the backyard fence as persons of inestimable value. And they in turn see you as performing a role not dissimilar to that of the pope. You’re not necessarily in front of an audience of millions, but those who know you and watch you in action come away inspired a bit and thinking the world is a better place because of you. Give yourself the grace to see that noble element that others see in you. Nurture it. Allow it to grow.

Good job! Keep it up!

More on the sacred work of meteorologists soon.

____________________________________________

[1] Quote Investigator tells us this is really an old Danish proverb. Yogi was Danish? Who knew?

[2] The great psychologist of risk, Paul Slovic, quotes Mother Teresa and adds this: “If I look at the mass I will never act. If I look at the one, I will.” This statement, uttered by Mother Teresa captures a powerful and deeply unsettling insight into human nature: Most people are caring and will exert great effort to reserve “the one” whose needy plight comes to their attention. But these same people often become numbly indifferent to the plight of “the one” who is one of many in a much greater problem.” The fuller article available by via the link is worth the read in its entirety. This same idea has been succinctly captured in a quote widely attributed (but again possibly falsely) to Joseph Stalin: “A single death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic.”

Bill, I love the way you find such interesting patterns in current events. Juxtaposing Pope Francis with Martin Shkreli, Donald Trump or even John Boehner, tells little. Connecting Yogi Berra, Pope Francis and the Hajj stampede speaks volumes. Thank you!