“The shortest period of time lies between the minute you put some money away for a rainy day and the unexpected arrival of rain” – Jane Bryant Quinn

Saving for a rainy day? Ancient wisdom.

Saving for a rainy day? Ancient wisdom.

But we violate this principle. Two stories in yesterday’s print edition of the Washington Post illustrate the point. The first, on page 2, was entitled climate scientists fear losing key tool at vital time.

You may know the story. Here’s a capsule from the article:

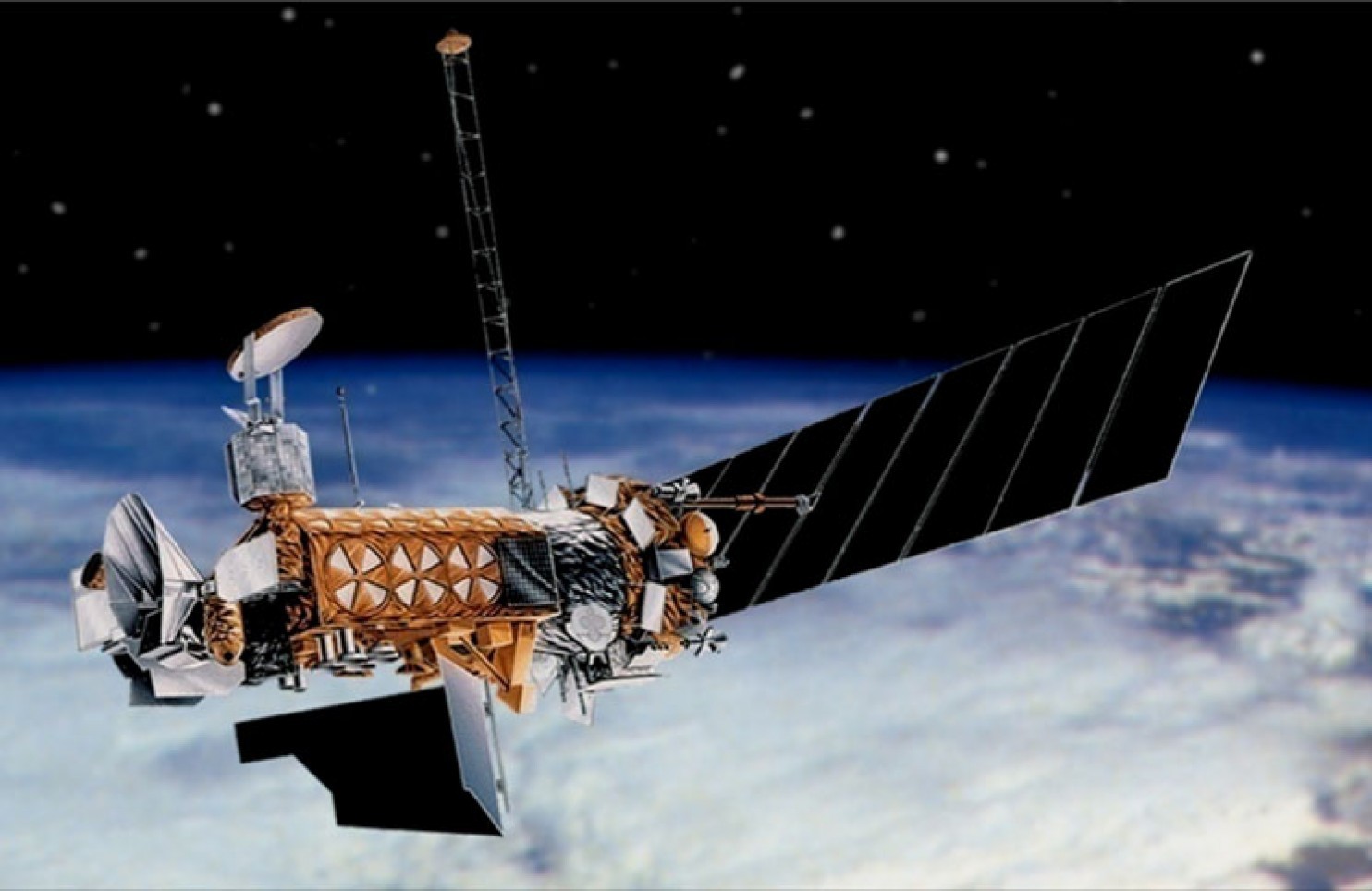

Earlier this month, a U.S. satellite known as F17 — which was primarily used for meteorological measurements — experienced operational failures that compromised the integrity of its data. And while there are similar satellites in orbit that can take over the data collection for now, they’re old enough that scientists are unsure how much longer they’ll last.

Now, with no government plans to launch a replacement any time soon, scientists who rely on these satellites for valuable climate data are beginning to worry about the future of their research. The problem comes at a vital time, too — one when the Arctic, and other remote regions, are seeing rapid changes and scientists badly need these instruments to track them.

The second, on page 3, headlined Zika crisis costs states funds for emergency preparedness. Again, the lead:

Cities and states preparing for possible Zika outbreaks this spring and summer are losing millions of federal dollars that local officials say they were counting on, not only for on-the-ground efforts to track and contain the spread of the mosquito-borne virus but also to respond to other emergencies that threaten public health.

Los Angeles County, for example, says it won’t be able to fill 17 vacancies at its public health laboratory or buy equipment to upgrade its capability for Zika testing. Michigan is concerned about providing resources to help Flint contend with its ongoing water-contamination crisis. Minnesota plans to reduce its stockpile of certain medications needed to treat first responders during emergencies.

The across-the-board funding cuts are part of a complicated shift of resources that the Obama administration blames on Congress and its refusal to approve the White House’s $1.9 billion emergency request to combat Zika. In early April, officials announced a stopgap measure that moved money originally intended for the government’s Ebola response.

But in that scramble, the administration also redirected about $44 million in emergency preparedness grants that state and local public health departments expected to receive starting in July. They use the grants for a broad range of events, including natural and human disasters and terrorist attacks. Some agencies lost up to 9 percent of their awards…

The links provide fuller details, but you get the idea. Limited in our resources, we make daily choices about our spending priorities as individuals and a nation. Time was, we said Earth observation from space was so important to both national security and public safety as to merit the redundancy of civilian and military observations. But in recent years we tended to reframe this as duplication and waste, and decided a single satellite system would do. In the same way, we’ve skimped on emergency response. As a result, the limited funding is continually reallocated – we chase the latest crisis.

(Two small quibbles with these articles. The first focuses on a collateral benefit of the military’s satellite versus the risk its loss poses to military operations worldwide – its intended purpose. Regardless of your stance and mine on the climate issue, we should mourn its coming end. The second article suggests that this reallocation of emergency response funding is something new. It’s not. Following 9/11, the primary federal funding for emergency response was focused on the terrorist threat. State and local governments found plenty of funding for hazmat suits, etc., but few funds for facing that rainy day – floods – or for earthquake preparedness.)

But the larger challenge remains: (1) ensuring the continuity of the vigilance that Earth observations of all types provide against threats of every origin, and (2) preparing and building resilience with respect to all contingencies, versus picking one and hoping we’re guessing right. What’s more, enhancing our investment in Earth observations and emergency response capability comes at small cost — let’s say one or two billion dollars more out of a federal budget of several trillion and a GDP five times that. In fact it saves money, following the lines of a second piece of ancient wisdom:

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

We can do better.

Your posting highlights one of the socio-cultural themes of the times – reactivity, followed by “hair on fire” decision making. It seems that collectively we have lost our capacity for reflection, strategic thinking and planning, and seeing a bigger picture. I agree that we can most certainly do better.

🙂 Thanks, Susan!

Bill:-

In a previous piece, you aptly quoted Gibbon:

“In the end, more than freedom, they wanted security. They wanted a comfortable life, and they lost it all – security, comfort, and freedom. When the Athenians finally wanted not to give to society but for society to give to them, when the freedom they wished for most was freedom from responsibility, then Athens ceased to be free…”

In each case you cite, it was the loss of federal funding that was the problem. But actually there are three causes that I see as the root of these problems.

• Kneejerk responses to the problem du jour. At the federal level, we don’t budget for disasters or contingencies. Many states and municipalities have reserve funds, why can’t the federal government? Instead, we have an orgy of borrowing fueled by near-negative interest rates, and “emergency appropriations” reflecting poor planning.

• Over-dependence on someone else’s money, esp. at the local level. If these things are that important, why can’t Los Angeles, Minnesota, or Michigan pay to fix their own problems? I know that sounds unfeeling (and actually may be impractical given the shaky financial situation in the Rust Belt) but we need to start weening the hogs off of the federal teat. Our grandkids won’t be able to afford the bill we’re running up.

• Finally – most importantly – where is the vision of a desired future, the will to strive for the vision, and the integrity to stay the course no matter how momentarily unpopular it may become? Ultimately, as Gibbon implies, we must all recognize that our freedom isn’t free – it requires that each of us must invest our own time, our own money and our own effort to attain the futures we desire.

GREAT comment, John. In fact, that’s not just a comment — it’s co-authorship. Thanks for a crisp, wonderful summation of the issues.