Physics Today’s July 2024 issue provides the happy news, in an article authored by Timothy DelSole and Paul A. Dirmeyer. They begin in this (excerpted) vein:

As senior scientists, we have navigated the challenging waters of the PhD qualifying exam—both as students taking it and as professors administering it. As students, both of us excelled academically, yet we anticipated the qualifying exam with anxiety and dread. How could we not? The professors judging us could inquire about any aspect on which they were expert…

…We recall preparing diligently for specific topics about which we were never queried, and thus we were unable to showcase our extensive preparation. We recall knowing the answers to some exam questions in retrospect, but in the pressure of the moment, we couldn’t remember them. What’s more, passing the qualifying exam left us no closer to defining our thesis research direction.

Later we discovered that professors also approach the qualifying exam with anxiety and dread. The consequences of the exam put immense pressure on professors to craft questions that can accurately gauge a student’s potential…

…And the fact that those judgments usually rest with a few faculty members raises concerns about fairness and the inclusion of diverse viewpoints…

They identify holes in the common justifications for the traditional process, then raise some counterarguments, before concluding that some kind of testing is needed:

…Despite those shortcomings, there remains a compelling necessity for qualifying exams: Experience shows that some students, despite passing their courses, struggle to complete a dissertation within the typical five-year doctoral program. Identifying those students early allows all parties to move forward without investing years of effort into a PhD journey that may ultimately be unsuccessful…

Sound familiar? If you are or ever were a graduate student in the physical sciences, you bet it does. Merely reading this and reflecting on those earlier days might even trigger a PTSD episode.

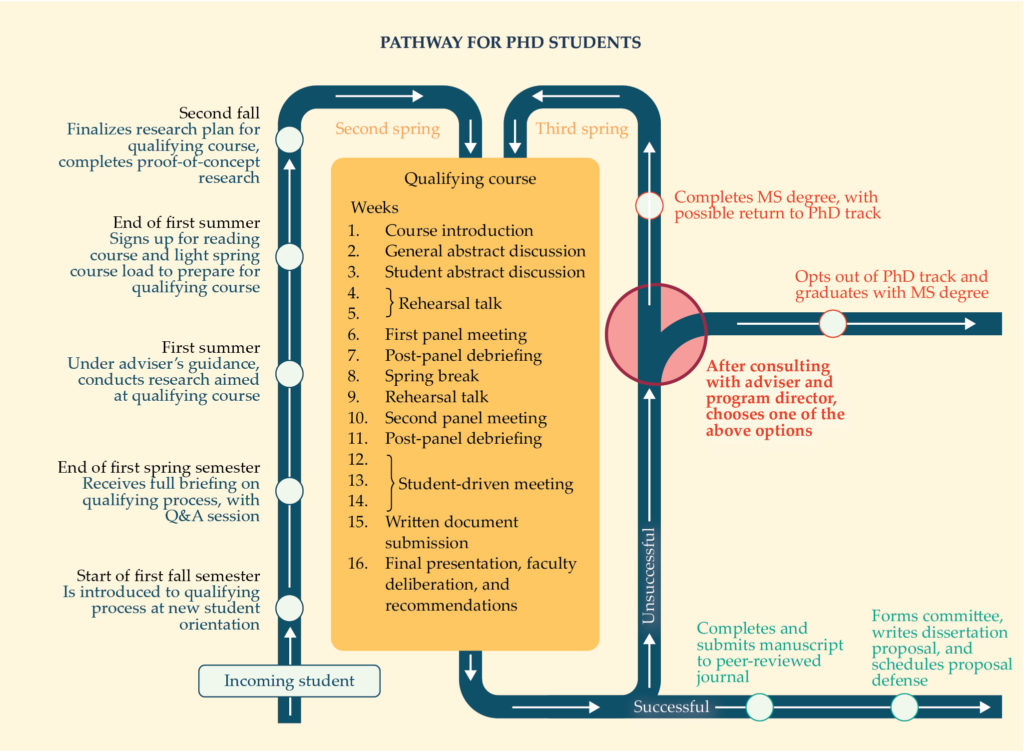

Delsole and Dirmeyer capture the novel, semester-long GMU process (as much a course as it is an exam) in a single flow-chart:

Physics Today, July 2024, page 34

They provide a detailed description in their article (which merits careful study in its entirety): To oversimplify: at the end of their first year’s spring semester, students work under an advisor’s guidance to conduct research aimed at the qualifying course per se (held in the spring semester of second year). From that point on, students’ second-year course load is shaped around the qualifying course, which leads them through an iterative sequence of research, punctuated by frequent presentations to and feedback from faculty and fellow students, and development and submission of a written document (that in the best-case scenario, for some truly exceptional students, will be suitable for publication in a peer-reviewed journal)

Delsole and Dirmeyer observe that

The new qualifying process has several advantages over the traditional format. First, instead of assessing a student’s knowledge, faculty members evaluate the student’s ability to perform the activities critical to scientific inquiry: identifying a scientific problem, devising solutions, and engaging in discourse. Second, the process spans an entire semester, so decisions on a student’s performance are not based on a singular moment. Third, each student chooses their own research topic, affording them the opportunity to showcase their creativity.

Furthermore, a student receives questions tailored to their chosen topic…

…The new qualifying process also offers each student multiple opportunities to succeed. (Two independent faculty panels; an additional written submission)…

…A…student has ample opportunity to revise their work…

…Unavoidably, subjective judgments affect the final decision, and they may be influenced by biases tied to race, gender, sexual orientation, or disability… In the new format, the entire faculty openly participate in the decision-making process, which brings a wider range of perspectives into the discussion.

By distributing responsibility across all faculty members, the new process also lightens the burden on individual advisers, who often hesitate to single out their own struggling students. When a student is redirected, their adviser usually appreciates the collective intervention.

Although the new format requires a greater investment of time from faculty, productive scientists are accustomed to allocating time for conferences and peer-review duties. And the new qualifying process calls for minimal preparation by faculty, with only modest tasks required post-meeting, such as filling out evaluation forms. When it comes to peer-review services, the question is how to best manage one’s time reviewing others’ work. Allocating a portion of that time to assisting students in one’s own department proves to be a sound investment in upholding the quality and integrity of the qualifying process. Ultimately, the efforts produce better student outcomes, which, in turn, cast a positive light on the faculty and the department.

They acknowledge:

Fellow scientists who hear about our qualifying process are often doubtful about its feasibility in their own departments. They cite factors such as a large student population. We are confident, however, that the new process can be tailored to any department. Our PhD program at George Mason has a dozen faculty members and admits three to six candidates per year. For larger departments, splitting students and faculty into smaller cohorts operating in parallel is a feasible solution.

Another concern has been the perceived inefficiency of involving faculty who lack expertise in a student’s chosen topic. But we have found the opposite to be true: Observing how the student articulates their research to nonspecialists, who nonetheless possess broad scientific knowledge, has several advantages. Incorporating diverse expertise in faculty panels, for instance, ensures that a mix of technical and foundational questions will be addressed, which makes the evaluation more thorough.

The new process also encourages faculty to engage with each student out of genuine interest, thus fostering a less adversarial interaction than the traditional approach. The reversal of the conventional roles of teacher and student mirrors what a student will encounter in advanced doctoral research. Furthermore, the shift in dynamic creates opportunities for a student to demonstrate creativity in handling conflicting criticisms that arise from reviewers with different knowledge backgrounds.

One issue that has generated considerable debate among our faculty is the grading policy. Currently, a student who passes the qualifying course receives either an A or a B. The A grade, however, is reserved for students who submit a manuscript that the faculty believes can be refined into a publishable paper after a few months of revision. That’s a high standard, and not all exceptional students meet it.

We believe that a significant distinction exists between a student who develops a nearly publishable paper in their second year and one who does not, and the grade assigned to each one is intended to reflect and reward that difference. Moreover, the standard is attainable: One or more students achieve it each year.

The authors and their GMU department have accomplished something truly extraordinary. They haven’t merely “fixed the qualifying exam;” they’ve transformed the graduate experience for both students and faculty. They’ve created (restored?) a new balance between research and teaching in the department. They’ve built true community – among the individual researchers, as well as between faculty and students. Issues of fairness and diversity have been addressed, not as artificial add-ons, but as an integral, natural part of the process. They’re not merely tabling a novel but untried idea; they’re reporting on its successful implementation.

And they’ve shared all this in a concise, comprehensive paper that is a model of clarity and compelling in its logic.

Bravo!

This novel GMU approach deserves to be widely copied and emulated by other geosciences faculty (and students!) on other campuses – and by other disciplines more broadly.

_______________________________________________

An aside on my personal graduate-school experience at the University of Chicago in the 1960’s: After graduating from college with a degree in physics in 1964, I started work at Chicago’s Institute for the Study of Metals for the summer, and then entered the University’s graduate physics program in the fall. After one year of physics I transferred to the department of geophysical sciences in the fall of 1965 and graduated with a PhD in the summer quarter of 1967. That trajectory was enabled greatly by my thesis advisor, Colin Hines (I’ve thanked him profusely and inadequately in a 2020 LOTRW post, on the occasion of his passing).

But the other major factor was the difference between the physics qualifying exam and its counterpart in the geophysical sciences. Back then, the physics qualifying exam demanded that students master that vast field in its entirety. By contrast (and I didn’t know this when I transferred – due-diligence about such things was not one of my strong suits), the department of geophysical sciences, though dealing with a far more limited literature and history, required of students only that they demonstrate their ability to learn facets of the science when and if they had to. Students worked with faculty to negotiate three fields of study on which they would be examined in several months’ time. The fields were chosen to be of some relevance to the student’s intended Ph.D. research. Faculty assumed that if students could demonstrate a certain level of proficiency in those areas, they could attain similar levels of mastery over other subjects as needed during their Ph.D. research or over their subsequent careers. The qualifying exam was linked to the student’s development of a thesis prospectus and standing for examination on that. As I recall, I was examined on ionospheric physics and chemistry, upper atmospheric dynamics (general circulation, atmospheric tides, gravity waves, etc.), and hydromagnetics (the general dynamics of conducting fluids).

Not by any stretch the polished, robust GMU approach, but containing early hints of something similar.