“Don’t build a town on the mountainside unless you like high stakes…”

The above line is part of the refrain from a blues number written and performed by none other than blogger Andy Revkin, following the 1995 flooding event in Boulder, Colorado; you can hear it here. Worth the listen, both for the substantive message and the music.

Last week far more damaging floods revisited not just Boulder but a string of towns and settlement lining Colorado’s entire Front Range. An unusual weather pattern dumped more than a foot of rain over the area – nearly a year’s worth in terms of the climatology of the region – in just a day or two. The rains flushed torrents of water down steep canyons, produced extended flooding out on the adjacent plains, took seven lives (at this count; area residents have been slow to report in), and inflicted a billion dollars of property damage and economic disruption (the estimates continue to rise, even as the flood waters recede). Jason Samenow and The Capital Weather Gang provide more numbers. The Denver Post has delivered and continues to offer extensive coverage (e.g., here).

Behind the numbers: tragedy for far too many, pain and suffering for everyone. Recovery may take a long time. Colorado winters can come early; if this one does, it will slow the return to life-as-usual. For some towns like Lyons, that “return” will almost certainly be to a new normal. The river cut a different path through the town; its residents and business owners face serious decisions in coming months.

Mr. Revkin’s high stakes are proving much higher this time around.

There’s been quite a bit of discussion about whether this was a so-called 100-year event, or something still more rare, perhaps even signaling a climate change influence. Roger Pielke Jr. has contributed a thoughtful perspective.

__________________________________

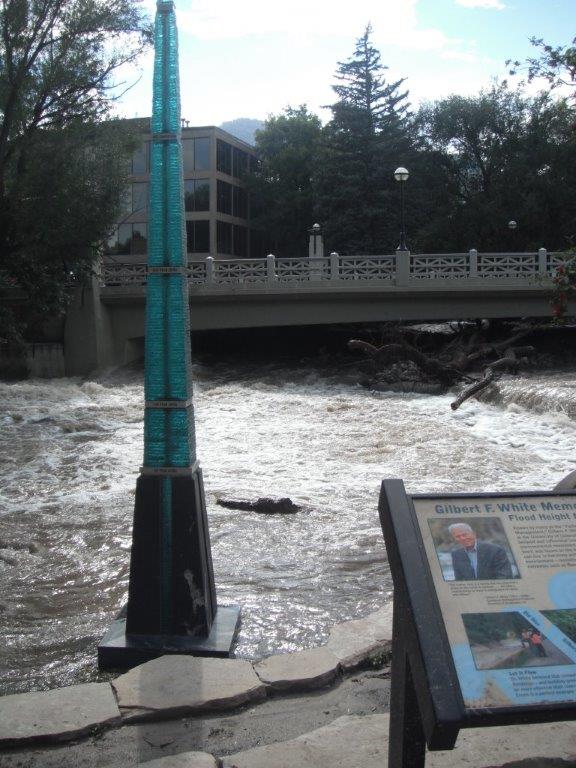

“Floods are an act of God, but flood losses are largely an act of man.” – Gilbert Fowler White (from his Ph.D. dissertation, “Human adjustment to floods.”)

Flooded Boulder Creek, near the intersection of Broadway and Arapahoe. A monument to Gilbert White stands in the foreground. Normally the base of the marker is well above the creek’s height. (Photograph kindly supplied by Diane Smith of NHRAIC.)

Flooded Boulder Creek, near the intersection of Broadway and Arapahoe. A monument to Gilbert White stands in the foreground. Normally the base of the marker is well above the creek’s height. (Photograph kindly supplied by Diane Smith of NHRAIC.)

Interestingly, but not surprisingly, Mr. Pielke invokes the name and work of Gilbert Fowler White, a renowned geographer, sometimes referred to as “the father of floodplain management.” White’s contributions were global, dealing with such existential issues as water resources as a human right and as a means to peace, and how to reduce the global toll of hazards. Nevertheless, he reserved a special place for his adopted home of Boulder, Colorado in both his heart and his brain. Throughout the latter part of his career, he repeatedly called attention to Boulder’s vulnerability to floods. Even he might have been surprised, however, by last week’s event that hit not just a single canyon-watershed, but a line of watersheds comprising numerous canyons over such a significant north-south extent.

In his life, Gilbert White exemplified a small truth; those who study the natural and social science of hazards tend to live in the shadow of those very threats – on the front lines, as it were. Large numbers of seismologists live and work along California’s major seismic zones, from Los Angeles up through San Francisco. Much of NOAA’s tsunami work is concentrated in Alaska and the Seattle areas. USGS maintains major volcanic observatories near Mount Rainier and on the big island of Hawaii. NOAA’s National Hurricane Center (NHC) is based in Miami. Tornado researchers are concentrate in Oklahoma and environs. The Center for Hazards Assessment, Response, and Technology (CHART) is based at the University of New Orleans. Similar clusters of hazard scientists can be found abroad.

The good news is that the locations provide a wonderful sense of urgency and immediacy to the work. Knowledge is firsthand. Passion and science get to coexist. The bad news is that when disasters strike, they disrupt or slow down the work of scientists and institutions at precisely the time when the opportunities are the greatest and most fleeting. CHART scientists and the University of New Orleans were hit hard by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. NHC and staff suffered a severe blow from Hurricane Andrew in 1992. And it isn’t just the work that suffers in such cases. Scientists lose homes and experience additional financial loss. Their health can be been affected. Volcanologists have lost their lives in explosive eruptions such as that of Mount St. Helens. Tornado experts have died in the chase of their quarry.

In the present instance, Boulder scientists at NCAR/UCAR, at NOAA, and the University of Colorado, numbering in the hundreds, are allocating their time between their research on monitoring and modeling weather extremes of the type they’ve just experienced firsthand and tackling jobs that were once routine but now pose challenges: getting groceries, cleaning out muck and debris from the flooding, putting the kids back into school, and more. Hazards researchers at CU-Boulder’s Natural Hazards Research Applications and Information Center (NHRAIC, which Gilbert White helped found) were all impacted. As Fort Collins struggles to return to normal, Colorado State University assistant professor Russ Schumacher and his precipitation systems research group are trying to collect physical and social data on the storm and its impacts. They’re leading the multi-disciplinary community they established in June of this year at their Studies of Precipitation, flooding, and Rainfall Extremes Across Disciplines (SPREAD) workshop. The object of their study, last week’s flooding in the Big Thompson Canyon, is a reprise of the disastrous 1976 event.

Others on the front lines researching hazards can expect their time to come. A risky business! We owe them all a debt of thanks for their perseverance and dedication. And we owe it to ourselves to take their findings to heart: to build our community (and family) resilience to hazards, to make ourselves weather-ready.

Thank you, Bill, for this wonderful column and for posting Diane’s picture. I too cannot get Gilbert and Boulder from my mind. It is not the time for me to go there, but i am so drawn there. THANK YOU!

Good to hear from you, Ann. Thank you for your unflagging efforts there on the front lines, building Tulsa’s resilience to floods…

Having been directly involved in the 1976 Big Thompson Canyon flood which killed 134 people and which came only 4 years after the Rapid City Flood of 1972 which killed over 200 people, we concluded at the time that every canyon along the front range of the Rockies was only one storm system from a massive flood. Thanks for calling attention to this again.

Pingback: Content on CO Floods – updated on Sept. 19 | Recovery Diva

Nice job, Bill. I have cited your post on my blog.

Claire