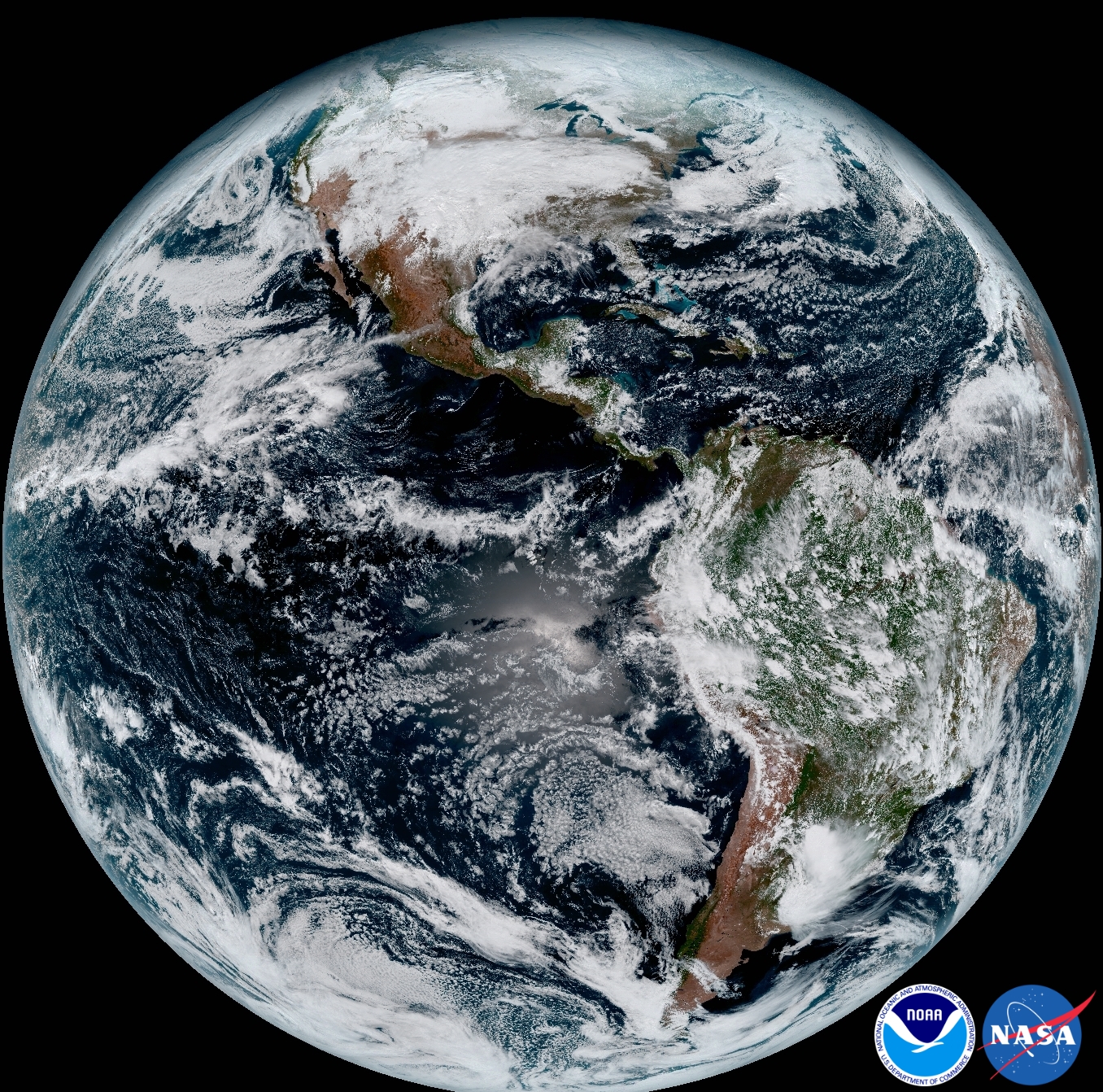

Earth as seem from Stephen Hawking’s rear-view mirror.

Stephen Hawking has been asking a proper question: How much time do we (humans) have here on Earth?

His answer is uncertain, and in fact has been a moving target, but can be summed up like this: not much! (and – maybe less and less, the more he thinks about it).

His suggested response option is by contrast definitive – and perhaps not the one you and I might prefer: time to leave!

Surely worth some discussion.

ICYMI, here’s some background, excerpted from a May 5 article by Peter Holley published on the Washington Post website (only one of many carrying the story, off and on over several months; you can find more material elsewhere on line):

In November, Stephen Hawking and his bulging computer brain gave humanity what we thought was an intimidating deadline for finding a new planet to call home: 1,000 years. Ten centuries is a blip in the grand arc of the universe, but in human terms it was the apocalyptic equivalent of getting a few weeks’ notice before our collective landlord (Mother Earth) kicks us to the curb. Even so, we took a collective breath and steeled our nerves. So what if there’s no interplanetary Craigslist for new astronomical sublets, we told ourselves, we’re human — the Bear Grylls of the natural order. We’ve already survived the ice age, the plague, a bunch of scary volcanoes and earthquakes, and the 2016 election cycle. We got this, right?

Not so fast. Now Hawking, the renowned theoretical physicist turned apocalypse warning system, is back with a revised deadline. In “Expedition New Earth” — a documentary that debuts this summer as part of the BBC’s “Tomorrow’s World” science season — Hawking claims that Mother Earth would greatly appreciate it if we could gather our belongings and get out — not in 1,000 years, but in the next century or so… “Professor Stephen Hawking thinks the human species will have to populate a new planet within 100 years if it is to survive,” the BBC said with a notable absence of punctuation marks in a statement posted online. “With climate change, overdue asteroid strikes, epidemics and population growth, our own planet is increasingly precarious…”

…Some of Hawking’s most explicit warnings have revolved around the potential threat posed by artificial intelligence. That means — in Hawking’s analysis — humanity’s daunting challenge is twofold: develop the technology that will enable us to leave the planet and start a colony elsewhere, while avoiding the frightening perils that may be unleashed by said technology. When it comes to discussing that threat, Hawking is unmistakably blunt. “I think the development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race,” Hawking told the BBC in a 2014 interview… Despite its current usefulness, he cautioned, further developing A.I. could prove a fatal mistake. “Once humans develop artificial intelligence, it will take off on its own and redesign itself at an ever increasing rate,” Hawking warned in recent months. “Humans, who are limited by slow biological evolution, couldn’t compete and would be superseded.”

Whew! A heavy lift.

Perhaps not surprising that Mr. Hawking should be the one to raise this question and suggest this path forward. He’s hugely bright – brilliant. And he’s used to thinking big-picture – cosmos, universe, origins, possibilities. He’s also British; they’re the folks who (just barely) brought us Brexit (and inspired all the other “exit” tropes).

For all sorts of reasons, we’re right to fret that our time here on Earth might be limited – that the Anthropocene, like the Holocene and Eocene, and every other “cene” before them, will someday come to an end, making it necessary for us to leave the scene (sorry, couldn’t help myself). And that requires some thought and effort be given to ways and means.

But only some thought. The vast bulk of thought and effort, the priority, should focus on buying time here – to extending the habitability of Earth. Buying that time, and how to go about it, have been central theses of this blog, going back to 2010, and the 2014 book by the same title.

To restate some of the core ideas: First, seven billion of us are not leaving the planet any time soon. That opportunity (and its associated risk) is going to be left to at most a privileged handful. Fact is, the current and future level of effort contemplated by Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Richard Branson might be about right, if we throw in an increment at NASA (the Chinese look to be adding more as well). The rest of us ought to be focused like a laser on the threefold problem of managing the Earth as a resource, threat, and victim.

That translates into “buying time” – a problem with several elements. Let’s look at three.

First, and simplest: estimating how much time we have. As Mr. Hawking’s thought process reminds us, that is not a single problem, but multiple ones: How much time until the first significant asteroid impact? Until some terrorist act or cold-war-type global power struggle triggers a nuclear holocaust? Until we run out of the supplies of yttrium or lanthanum or praseodymium or neodymium or any of the rare earths we need for today’s IT? Until we run out of food or water? Until a virus goes globally out of control? Until the sheer weight of thousands of environmental insults renders the planet uninhabitable? Until some cyber-catastrophe our relations with each other become so toxic that life is no longer worth living? The problems are legion, complex, and interconnected. Which are most urgent, and why?

Second, and more daunting: thinking through the options. How to buy time – an extra day, or year, or century? Investigating: how can economics and substitutability help? New technology? New lifestyle? What are the choices? What is the cost of each? How much time does it buy? What are the implications for the other timelines? Thinking in terms of triage: what must be done now? What can wait? What challenges look hopeless based on what we know now?

Third, and most expensive and demanding in terms of level of effort, taking action. That doesn’t demand reaching consensus on what to do (too difficult in today’s world, and actually dangerous given the risk of making bad choices), but vigorous exploration of diverse approaches, paying attention to early detection of success and failure.

A few closing comments (maybe more than a few).

First, we’ve seen this movie before. The ozone hole. Acid rain… ________(write-in your favorite here). And just as each version of Star Wars or X-Men tops its predecessor in scale and sweep, so it is with Living on the Real World. The climate challenge that has the world in its thrall today is far more imposing than these prior concerns. But this Buying-Time problem is larger still. As Stephen Hawking notes, it’s truly existential.

Second, perhaps the biggest advantage Buying Time holds over E(arth)xit is global involvement. E(arth)xit fully engages the skills of a mere handful. Perhaps the richest 0.1%. (The money has to come from somewhere). “Rocket scientists.” They’re needed to make the venture physically possible. A few biologists. After all, the solar system’s options (the most within-reach) are hardly Goldilocks planets; they’ll require quite a bit of planetary-scale tinkering before they’re well-and-truly habitable). And social scientists, addressing questions of how we choose those who will “boldly go where no one has gone before,” versus the seven-going-on-nine billion of us who will stay. (In the Brexit terminology, “leave” versus “remain.”). All the social science says that social risks of such extended high-stakes space travel outweigh the other threats.

All that may sound like it adds up to a lot of people. But most of the seven-going-on-nine billion of us will be bystanders, spectators. We won’t be participants. And we’ll be unhappy, critical spectators. We’ll see most of the resources – including the world’s intellectual resources – tied up in the support of a few rather than solving real-world problems of hunger, poverty, jobs, health, and more. If most of us are critical, unhappy, some will be dangerously so, sabotaging the effort in ways ranging from hacking to acts of terror.

By contrast, Buying Time calls for full global engagement, action-in-place. There are no spectators. Everyone is a participant.

Years ago, Robert Townsend, the head of AVIS, the rental-car company, wrote a little management book entitled Up the Organization: How to Stop the Corporation from Stifling People and Strangling Profits. The tone was tongue-in-cheek, but contained a few pearls. One was that it was better to make sure all the managers were overworked; then they wouldn’t have time to notice they were being treated unfairly, or to criticize each other, or to complain that they deserved greater responsibility, etc.

There are parallels here to the “climate-change-movie.” Mitigation approaches – hitting the CO2 off-switch – are necessary, but as we’ve seen, leave most people uninvolved, and many, as we’ve discovered to our cost, critical, some harshly so. By contrast, and as a complement, climate adaptation is more necessarily place-based, exploratory – and it draws more people in. Instead of criticizing each other, you and I are free to pursue our own better ideas. A far more productive use of our time.

Third, and finally Buying Time has a track record of success. Century after century, and in arena upon arena – food, energy, water, transportation, waste management, global ingenuity has successfully bought time. We know how to do this.

So E(arth)xit merits some thought, some effort, considerable effort. Stephen Hawking is on to something. A complete strategy requires it. But the world attention should be on remain: sharpening up our estimates of how much time we have and why, identifying our options for buying time, exploring those, quickly detecting and sharing early signs of failure and success – and daily celebrating every bit of progress on the latter.

In this scenario, each of us matters. Each is essential. Time to step up and play our indispensable part.