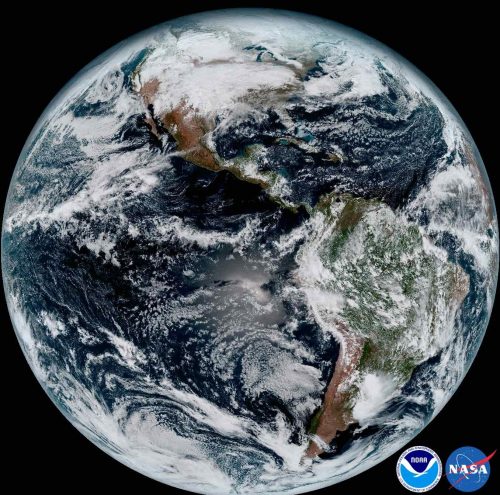

A recent GOES-16 image

“A Goldilocks planet is a planet that falls within a star’s habitable zone, and the name is often specifically used for planets close to the size of Earth…

…In astronomy and astrobiology, the circumstellar habitable zone (CHZ), or simply the habitable zone, is the range of orbits around a star within which a planetary surface can support liquid water given sufficient atmospheric pressure.” – (not quite random Google search result)

Suppose we’d been called into existence before the planet we live on had been created. Suppose further that we’d been asked to design and build a spaceship on which we could tour the universe.

Never in a million years would we have come up with a totally cool open-air convertible.

But, wow! That’s what we’ve got. And it’s amazing. It’s perfect for us. It’s got everything we want or could ever want. You and I could blog for a million years of days and write a billion pages and not even begin to capture all the wonders that make it ideal. It’s cause for celebration! And that’s what we’re doing. In a way, what the world’s peoples do all day every day – as we dialog and rub shoulders with each other, as we put our hands and brains to every kind of work and recreation, as we contemplate and create and innovate – we share and rejoice in our good fortune in one way or another.

Throughout our history, our Earth has inspired us with this wonder, but it’s only in the past century or so that we’ve even begun to comprehend not just how magnificent it is, but also how remarkably unusual it is (and how fragile!). So far, our tour of the universe has shown us that the planets meeting these conditions even approximately are few and far between. We won’t be pulling alongside another such planet on our celestial tour anytime soon.

For all of this recent period of awareness each and every one of us has since childhood had the story of Goldilockand the three bears to capture the imagination. So it was natural to apply this name to our astronomical investigations. But remember this: Goldilocks has more to offer us than a label. She offers a cautionary tale. In today’s 21st-America, at a time when we’re toying with rollbacks of this and that environmental regulation, we should revisit and learn from her mistakes. Some of the lessons:

Ownership. Goldilocks was where she didn’t belong. The house she entered belonged to the three bears, not to her. In the same way, as we tour the universe in our remarkable convertible called Earth, we shouldn’t assume we have any bragging rights. We can’t say to those we pass: “look what we made!” Objective observers would more likely see us less as astute designers and builders and more as joy-riding adolescents thoughtlessly trashing the car’s interior…

…over-eating. Goldilocks was okay sampling the porridge. But when she consumed the baby bear’s entire bowl, she got the bears’ attention. In the same way, we need to learn to sip at natural resources, focusing on that which is renewable, and showing careful stewardship of that which can’t be replaced.

…and spoiling our nest. Just by sitting, Goldilocks made a noticeable impact on the bear’s chairs. In the same way, seven billion of us, though meaning no harm, have compromised Earth’s ecosystem services, especially over recent decades as our numbers have grown and our per-capita consumption of resources have increased.

Whatever you do, don’t fall asleep at the switch. The carbs in the porridge and the comfort of the chair enticed Goldilocks to take a little nap. Just a little one! But in letting the dopamine do its work, she was also allowing herself to be delusional, to fantasize that all was well. Goldilocks persuaded herself that she wasn’t in the house of strangers, that the food she had eaten would be magically replaced by more by the time she woke up, that she wouldn’t be noticed, that no threats would appear before she woke up. All these realities she pushed aside.

That was her undoing.

In the same way, several billion of us (not the whole seven billion, but only the most advantaged) have grown accustomed to the privileges we enjoy: an abundance of food of endless variety at the market, pure water flowing freely from every tap, reliable electrical power at every outlet, and ample gasoline and natural gas at every point of need. Clean air, clean water, a grand experience of the richness and variety of nature filling our senses. Safety in the face of natural hazards. Instead of being awestruck, we’ve grown complacent. Instead of being grateful, we’ve felt entitled. Instead of remaining thoughtful and vigilant, we’ve yielded to carelessness.

There’s no other way to explain a kneejerk aversion to phrases such as “climate change” and “environmental protection” and “renewable energy;” mindless rollback of environmental programs and initiatives, with little more thought than a cursory word search reveals such phrases; and obsessive, misplaced attempts to root out such terms and the ideas behind them in public education, news media, and more, wherever they appear. We know humans are capable of this mindset – making terrible decisions and committing horrible acts on the basis of mere labels rather than substance. Examples such as the Spanish Inquisition, the Salem witch trials, and the Holocaust are ever before us. But history‘s rearview mirror shows us that such lapses have always proven unspeakably destructive.

Fortunately, history has also shown that that such aberrance has been confined, both geographically, and to small subsets of the prevailing culture. Universally, people come to view such events as abhorrent.

This is where the final lesson of Goldilocks comes in:

Not too hot. Not too cold. The contrarian theory is alive and well. When President Richard Nixon visited the People’s Republic of China in 1972, beginning the process of formal recognition, it was an easy step politically. He was a known conservative and people trusted his judgment in this respect. Had George McGovern, a known liberal, been elected president instead, the public would have been distrustful and unaccepting of the initiative; they’d have seen it as a pinko-Communist move. In the same way, it was possible for Nixon to establish NOAA and EPA. In 1970, everyone could see this was a responsible step. Later, George Herbert Walker Bush when president would find it easy to support reauthorization of the Clean Air Act, allow the Montreal protocol to come into force, and to negotiate the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. But throughout the 1990’s, when Vice President Al Gore was saying that climate change was the defining problem facing humanity, Americans decided they were unconvinced. In 2001, the pendulum would swing the other way. The newly elected president, George W. Bush, thinking he was playing to the crowd, essentially said to the American people, “You’re right! Climate change isn’t a problem.” But instead of congratulating him and patting him on the back, the same American people said, “Wait a minute! We don’t think you should be that complacent about where we seem to be headed.” President Bush had to hurriedly convene an National Academy panel to reflect; after he received the findings he spent effort walking back his earlier stance.

Yesterday’s White-House ceremonial environmental rollbacks, both those announced and those otherwise implied, will almost certainly trigger the same reaction, and have the same political effect. The domestic reaction this morning is already quite negative. Abroad, the message is one of dismay, and a clear signal that the rest of the world remains reality-based and committed to pressing on.

What’s needed is an approach to these challenges that is just right – not too hot, and not too cold.

Instead of rhetoric claiming this is the challenge that will define humanity – or that this is fake news and can be dismissed out of hand – we need a middle course. We should recognize that the problems, though real, and requiring attention, need not consume us. We’ve estimated the associated infrastructure problem to be five percent of world GDP – something like $100T over the next twenty years (I promise this is the last time I’ll mention this figure – at least for a while.) Maybe another $100T will be needed to get a few other bits right with respect to spaceship-Earth maintenance over the same period. But that still leaves $2 Quadrillion dollars available over the same period for other things. And at the end of that time, world GDP will be a significant fraction of one quadrillion dollars annually.

But we can’t afford to fall asleep, as Goldilocks did. We need to enter the future with our eyes open, seeing what’s coming next. New opportunities for renewable resources, and new ways to conserve the nonrenewable bits. New ways to build resilience to hazards and preserve ecosystem services.

Thus the most essential critical infrastructure is therefore that which we need to guide our other critical infrastructure investments. For this, we need environmental intelligence, the observations to see how the Earth and its ecosystems are trending, predictive science able to anticipate what comes next, and policy formulation capturing the benefit of this information. Eyesight – Earth observations, science, and services – is the critical infrastructure we most need, if we are to keep the $100T from being a sunk cost, and convert it into a sound investment offering rich returns. The good news? Currently we’re only spending 0.1% of GDP on such situational awareness.

Now is NOT the time to deliberately blind ourselves – to pull the rug out from under this inexpensive but essential research, observations, and predictive understanding we need to move forward. Instead, since we’re not where we need to be, we should easily double-down on such critical infrastructure.

The real lesson from Goldilocks? It’s not about an emotional elimination of “unnecessarily burdensome regulations.” It’s about seven billion people moving in fits and starts, but on the whole, remaining committed to shouldering responsibility and demonstrating self-control – and doing so intelligently.