Let’s review.

Are you living on the real world? Do you want to make that life – your life – effective? Do you want your life to matter? If so, Stephen Covey advises, you’ll be proactive. You’ll see the world for its true vastness, its powerful trends, its turbulence and complexity – and within that, you’ll see your circle of influence – the bits you can (and should!) change for the better. And you won’t lose sight of your long-term goals – the ends you have in mind, both personally and professionally.

But then, Stephen Covey says, you must take a third step. There’s no shortage of the actions you’ll need to take day-by-day, month-by-month, and year-by-year, to achieve your ends. Chances are good you may not have fully thought these through. You must therefore clarify these actions in your own mind. You need to articulate them, sequence them. Which steps come first? Which can only come later? You need to plan. Note that because these are your ends, there’s no external urgency associated with them. You set the schedule[1].

At the same time, you operate within a context of necessary actions that are more-or-less imposed on you by that larger world. Showing up for work/doing your job. Paying your bills and your taxes. Keeping the fridge stocked. Raising children if you have them. These categories, and the individual actions within them, whether large or small, vary in importance. But the larger world, not you, sets the schedule. Sooner or later, if left unattended, they all become urgent. Finally, there’s so-called me-time.

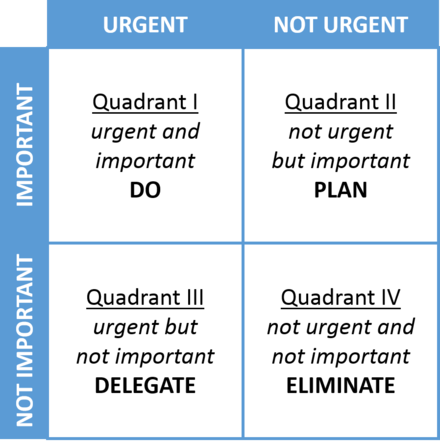

Hmm. We’ve backed into the four-quadrant picture, sometimes called the Eisenhower matrix (he claimed he got it from a former college president). Eisenhower used to say he had two kinds of problems, important and urgent. And he would add that the important were never urgent, and the urgent never important.

In the context of this matrix, Stephen Covey argues that we want to spend as much energy/effort in the important/non-urgent quadrant as we can; devote the time/energy to the important/urgent quadrant that we must; do no more in the urgent/unimportant quadrant than we need to get by; and do all we can to eliminate the time we waste in the unimportant, non-urgent quadrant.

A couple of points. First, Covey argues that toward this end, it helps to schedule our priorities versus prioritize our schedules. (you can find commentary on this distinction here.) Second, it might seem that those life-ends have no urgency, but the fact is that they do. Tim Urban’s masterful 13-minute TED Talk Inside the Mind of a Master Procrastinator drives this point home, hilariously and effectively (just what the doctor ordered in these turbulent times). Finally, you really do want to reduce greatly the amount of time you’re wasting. And this is both subtle yet fundamental. Turns out that one contributor to wasting time in this quadrant is the daily accumulated stress of operating in the other quadrants. And much of this stress is self-imposed, not external. That means we can do more to minimize it. Here’s a maxim that might help, especially if you’re able to meditate on it, live it out: Instead of resting from your work, work from your rest. This draws strength from Mr. Covey’s first two habits. When you and I are thinking and working proactively, based on our internal end goals for our lives, we are in a more peaceful, relaxed, and effective posture than when we are reacting willy-nilly to someone else’s priorities. And to the extent we’re taking care of those important but externally-driven priorities before they become urgent, we are also more effective. Reminds me of the wall sign in the workshop of the Boulder lab where I had my first government job: lack of planning on your part does not constitute an emergency on my part.

To be crystal clear. Careful attention to and execution of Habit #3 is both more challenging and more vital in the year 2025 than it was in 1989 when Mr. Covey wrote his book.

In closing, a confession. I might be the last person who should be holding forth in this vein. In this instance, you should be doing as I say, not as I do. One of the first management courses I ever took was a 1976 two-day course entitled time management. As I’ve told people for the past half-century, my wife-to-be was handling the on-site arrangements for that course. We were married seven weeks later – and she’s been managing my time ever since. (Meanwhile) one of her instructor’s sobering lines? Most of you will sit through this course, and you won’t put it into practice. You are time slobs – and you might as well admit it.

Too true. Later, for most of my AMS years, I had a boss who was a master at getting things done. At one point, early on, he shared with me he owed a lot to David Allen’s book by that title. He even gave me a copy. (A gentle-but-not-too-subtle hint?) At the time, the approach was paper-based (it now accommodates paperless/electronic means) and it wasn’t my cup of tea. I gave the book to co-workers, and noticed that their reaction was positive and that uptake was rapid and noticeable. Over time, I gave the book a (more-open-minded) re-read, to find that its message had grown on me. That said, implementation has been a continual struggle. I have not one but two copies of the book, but only fragments of Allen’s methodology are in evidence in my workspace. Sigh.

[1] This presentation leaves the impression that the first three habits follow a linear sequence. That’s an oversimplification. The reality is you want to be cycling through these first three steps, iteratively refining or redefining them, on some kind of regular rhythm.