“Don’t you know you can’t go home again?” the author Ella Winter[1]

“No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.” – Heraclitus

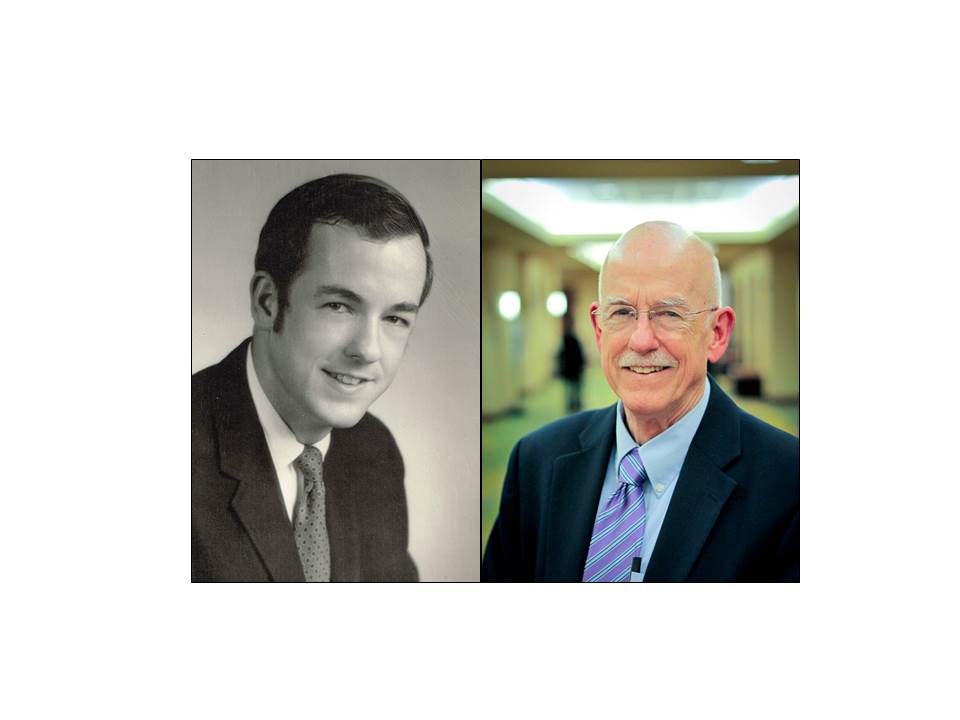

Today I make passage through sloppy winter weather prevailing along on the Middle Atlantic Coast to visit my alma mater, Swarthmore College[2]. Extra credit if you can tell which of the photographs below is from my senior yearbook and which is more recent: There I’m scheduled to give an after-dinner talk to a small discussion group. Here are the title and abstract:

There I’m scheduled to give an after-dinner talk to a small discussion group. Here are the title and abstract:

How Meteorologists Will Help Save the Planet:

Seven billion of us struggle daily to relate to our Earth—as a resource, as a threat and as a victim. Meteorologists are trained and well equipped to cope with chaos, disasters, and extraordinary events, but they also can take a long-term view. Bill Hooke will discuss how weather forecasting can be used to find solutions for many of our pressing 21st century challenges.

Both bits are shortened versions of what were originally proposed, and represent, depending upon how charitably disposed you might be, compromises – or maybe even egregious misrepresentations – with respect to what I’ll actually say. Many readers will recognize these as truncated versions of the title of my recent book and of the thoughts therein – forced to fit within the length constraints imposed by the marketing blurb for this year’s series of such monthly discussions. To be fair to the program organizers, I was given final say on the wording, so responsibility for that rests with me.

Indeed, that is my lifelong problem — inadequate scholarship. Fifty-four years ago, in late September of 1960, I arrived on Swarthmore’s campus to begin my freshman year. Back then the student body numbered only some 900, compared with today’s figure of slightly over 1500 (at this rate of growth, we’ll be comparable in size to today’s Big Ten Universities in, say, 200-300 years). My high school at that time had a much larger student body. I’d been a nerdy figure in that high school. If a girl approached me in those days, I knew she had a math problem. And I’d always been cut from the sports teams. But in some special mix of youthful enthusiasm and delusion in transit I had wondered at times whether I would

(a) be one of the smarter (and more social) students at Swarthmore,

(b) be one of the better athletes,

(c) achieve both distinctions.

What a dreamer! At the start of my first lunch during freshman orientation in the college dining hall, it was immediately apparent that the correct answer was:

(d) none of the above.

That incoming freshman class numbered maybe 280. Some 179 of them had earned one or more varsity letters in high school; dozens of those students had lettered in multiple sports. Class intellectual and academic achievements were totally off the charts. (For the next four years, no one from either gender would ask for my help with a math problem.) Moreover, judging from the dining hall chatter, it felt as if everyone else already knew each other. It was time for a new goal: mediocrity/survival.

That freshman orientation was a rude awakening. But the academic regimen was even more daunting. Standards for what constituted logic, proof, evidence seemed impossibly high. And it wasn’t enough to achieve those standards in a single subject of study. This was, after all, a liberal arts college. We were supposed to master multiple disciplines, integrate, be generalists. I was forced to confront how poorly my high school had prepared me, and how lackadaisically I’d approached my education up to then. I’d been coasting. Even worse (how did I miss getting the word?), at the time the attrition rate at Swarthmore was 25-30%[3]. Spent my four years there scrambling to avoid that fate. But another statistic was in my favor. Half the men at Swarthmore participated in interscholastic athletics. Those odds allowed me to play a freshman season of JV baseball (first base) and a sophomore season of varsity and JV basketball (bench-sitter).

Two milestones over the intervening decades of recovery? One was running across the Darwin quote you’ll find on the home page of LOTRW. The other was a seminar I sat in on while working as a NOAA scientist in Boulder. The speaker on that particular occasion was an eminent dynamicist, today a member of the National Academy of Sciences. In the course of a brilliant presentation, he paused for a moment. “I’m not going to justify this next step,” he said, “but I will tell you what I did.[4]” In each of these instances, I found a special grace. Not every statement, oral or written, had to be justified by the fullest scientific rigor. If something less, it had only to be fully and publicly disclosed for what it was. That grace has allowed me over the past two years to write a book of chock-full of such conjecture.

Now to see if this time around, that Swarthmore culture will prove equally or more accommodating!

[1] in a conversation with another author, Thomas Wolfe, in the process inspiring the title of his posthumously published book, You Can’t Go Home Again.

[2] graduated with an S.B. in Physics (Honors) in 1964.

[3] Today it’s maybe only half that.

[4] Both are described in more detail in the very first LOTRW post, dating back to August 3, 2010.

Ah, Swarthmore. I well remember your fervent cheers as we beat the snot out of you on the football field…

“Fight them vehemently – Beat them severely – Rah.” [I always felt sorry for your cheerleaders!]

As a graduate of F&M (BA Chemistry, ’68), another great liberal arts college, I found myself better prepared for and in graduate school than my peers from the big mega-universities. Something about having to think about your answers rather than giving rote replies got us ready for the intellectual rough-and-tumble to come. The fact we had a broader perspective didn’t hurt, either.

🙂 Great comment, John:

You mentioned Swarthmore College cheers. Here’s another:

Bash ’em, smash ’em, gnash ’em Quakers,

grind ’em in the mud.

Shake ’em, break ’em, quake ’em Quakers,

we want blood.

Kill, Quakers, kill!

It’s a good thing for both institutions that their academics were better than the football teams they fielded.

LOVED this, Poppers! How’d it go?