A week ago, I ran into a long-time USACE colleague in the supermarket. We started out the way people of our generation do: “I’m thinking of retirement,” he said. “I’m pushing seventy.” “I’m pulling seventy,” I replied. Then we talked shop. Oroville was fresh in our minds. “Nobody here knows how to build a dam anymore,” he said. “But China’s building some three hundred dams around the world,” I replied. We chatted on that thought a few moments before going our separate ways.

Recent LOTRW posts have focused on the world’s need to invest in $100 trillion of food, water, energy, and other types of critical infrastructure over the next two decades. Some of this will be refurbishment – repaving and widening roads, replacing existing but aging rail, bridges, ports, water delivery systems, and more. Some of this will be new: high speed Internet, high-voltage DC electrical grids, solar and wind energy systems, etc.

All of it will be critical, in two important respects. First, the infrastructure is necessary to day-to-day and even moment-to-moment needs of seven billion people. Any interruption of services causes social upheaval. Though this is “well-known,” in recent years governments, utilities, and related private-sector service providers have become so skilled at meeting the need for continuity that all of us – you and I – have lost a palpable sense of vulnerability, and realistic appreciation for the complexity and cost of the task. Hence, questions such as “Why do I need the National Weather Service? I get my forecasts from The Weather Channel.” “Why do we need farms? I get my food from the supermarket.”

But second, such modern, up-to-date infrastructure is critical to the continued labor-force productivity growth we need if we are to compete economically and maintain U.S. standing worldwide.

Turns out we’ve suffered memory loss in this respect as well as well. This latter has been documented by Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson in their book American Amnesia: How the War on Government Led Us to Forget What Made America Prosper. They point to a time in post-World-War-II America when government and the private sector were in mild tension but for the most part worked cooperatively. They argue this partnership was responsible for huge labor productivity increases, thanks to infrastructure investments such as the Interstate Highway System. They go on to suggest that around 1980, this synergistic balance began to break down. Moderate business and Republican voices were drowned out by those holding more radical views. According to Hacker and Pierson, the new business ideology didn’t blame deindustrialization or foreign competition for the challenges of the time; instead the enemy somehow became our own government. In consequence, government-business synergy declined, and U.S. productivity growth – and competitiveness – dramatically slowed in like measure.

This matters, because $100T of critical infrastructure investment translates into jobs – a lot of jobs. Recall that this figure amounts to some 5% of global GDP over the same two decades. Give or take, that should translate into jobs for a comparable fraction of the global workforce. Wikipedia provides this background:

Global workforce refers to the international labor pool of workers, including those employed by multinational companies and connected through a global system of networking and production, immigrant workers, transient migrant workers, telecommuting workers, those in export-oriented employment, contingent work or other precarious employment. As of 2012, the global labor pool consisted of approximately 3 billion workers, around 200 million unemployed.

In other words, critical infrastructure investment alone should likely keep some 150 million workers occupied for twenty years – coincidentally comparable to the size of the unemployed group. Since we’re talking infrastructure, most of those jobs will be in-country. That’s good news. There are sizable pockets of unemployment in every country, and studies show it’s the unemployed, particularly the young unemployed, whose frustrations foment unrest and in extreme cases terrorism worldwide. Give young people jobs, and hope for a better future, and the fear and anger dissipate.

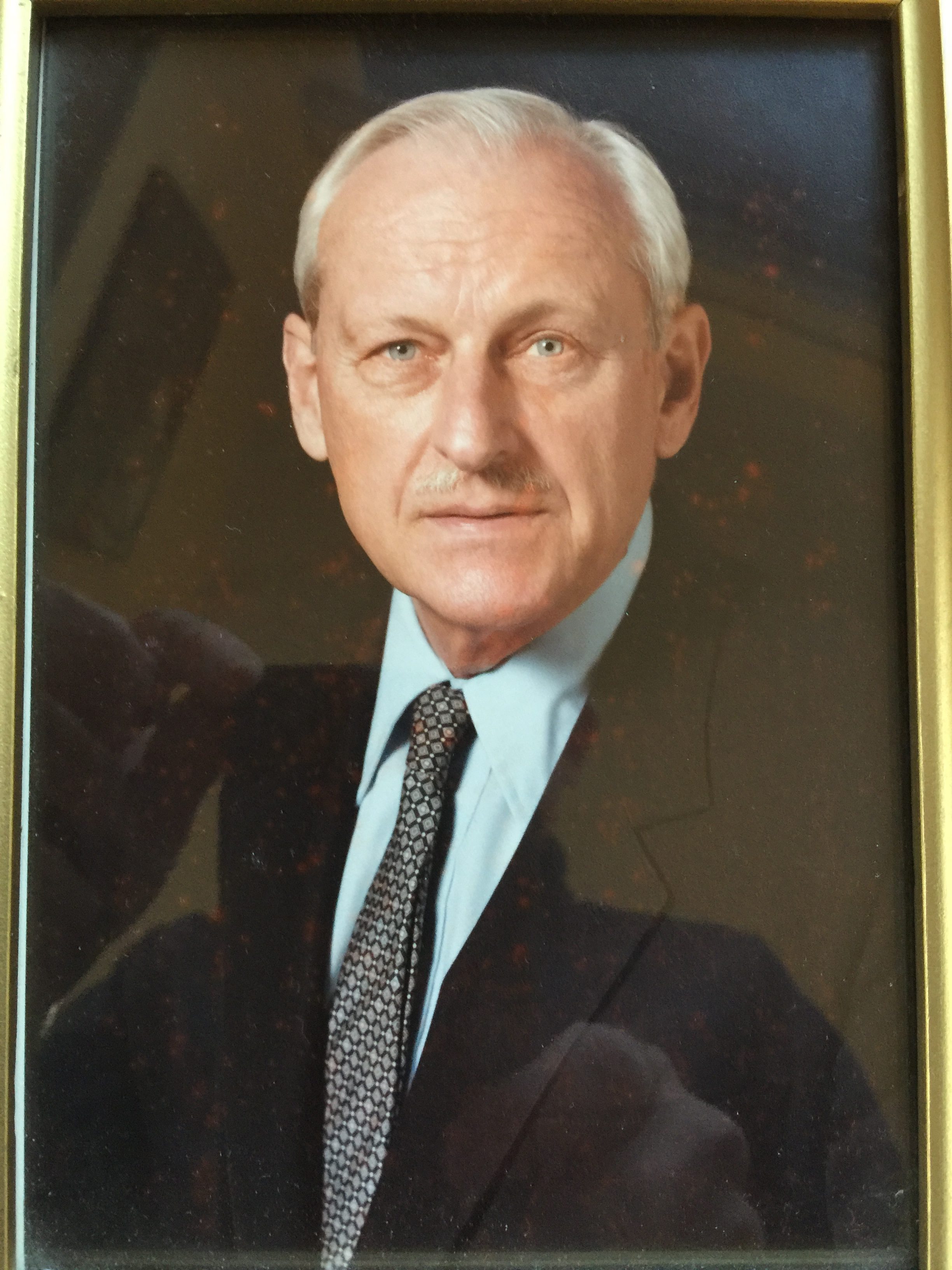

Although most of the jobs will be in-country, the project design and leadership, especially for the biggest projects, devolves to a handful of firms and nations worldwide with the needed expertise. In the years following World War II, thanks to its attention to domestic infrastructure, the United States was also preeminent across the world in big infrastructure projects. My father-in-law, Leigh Hill French III (pictured), was a case in point. After serving in the military during the War (he was at Normandy on June 6, 1944, but had the good fortune to go onshore at 6 p.m. instead of 6 a.m.), he used his civil-engineering background around the world for a variety of employers – building a port in Sumatra, an aluminum smelter in Greece, a dam in the Ivory Coast, as well as other similar projects from Liberia and Ghana to Australia and Guam – with a university in Libya thrown in.

Although most of the jobs will be in-country, the project design and leadership, especially for the biggest projects, devolves to a handful of firms and nations worldwide with the needed expertise. In the years following World War II, thanks to its attention to domestic infrastructure, the United States was also preeminent across the world in big infrastructure projects. My father-in-law, Leigh Hill French III (pictured), was a case in point. After serving in the military during the War (he was at Normandy on June 6, 1944, but had the good fortune to go onshore at 6 p.m. instead of 6 a.m.), he used his civil-engineering background around the world for a variety of employers – building a port in Sumatra, an aluminum smelter in Greece, a dam in the Ivory Coast, as well as other similar projects from Liberia and Ghana to Australia and Guam – with a university in Libya thrown in.

Today, it’s China that is visible and active in this arena. The March 1 print edition of USA TODAY ran this story: China eyes global economic leadership as U.S. turns inward.

Some excerpts:

This year, a 300-mile railway will begin slicing through Kenya, cutting travel time between the capital, Nairobi, and one of East Africa’s largest ports, Mombasa, from 12 to four hours and breeding hopes of an economic and tourism revival in the region.

The country’s most significant transportation project since its independence in 1963 is being built courtesy of China. China Road and Bridge, a state-owned enterprise, leads construction of the $13.8 billion project, which is financed nearly 100% by the Export-Import Bank of China.

The railroad is one of a host of infrastructure projects China spearheads around the world in an ambitious quest to reinforce its emergence as the world’s next economic superpower while President Trump turns his back on globalization…

…China’s outward foreign direct investment totaled $187.8 billion in 2015, a record and a 52.5% increase from a year earlier, according to the World Bank. Ten years ago, its outward FDI stood at about $17.2 billion. The U.S. FDI — though still significantly larger than China at $348.6 billion — grew only 1.5% year-over-year.

China’s economic ascendance from poverty is a model for struggling nations eager to modernize rapidly, too. In helping to create wealth abroad, China gets an early say in the formation of markets for its exporters to sell…

The range of projects China has launched is eye-popping:

- New Silk Road: China’s modern version of the ancient East-West trade route — known as One Belt One Road — winds its way through Asia, the Middle East and Europe. Launched in 2014 with $40 billion of initial investment, it entails new or reinvigorated railways, ports and roads that will link key cities. The anticipated total investment could top $4 trillion, according to The Economist, citing Chinese government officials. “People don’t’ seem to realize how important it is,” Bottelier says. “A (freight) train is already running between London and China.”

- Pakistani infrastructure: Chinese President Xi Jinping arrived in Pakistan in the spring of 2015 and announced $45 billion worth of investment projects in energy and infrastructure development, some of it tied to the new trade route.

- Nicaraguan canal: In 2015, Wang Jing, a Chinese billionaire who made his fortune in telecom, began digging in the city of Brito, Nicaragua, in hopes of building a canal that will cut 170 miles across the country and ultimately compete with the Panama Canal. The project stalled as his fortunes sank along with the Chinese stock market, but it has not been abandoned.

- South American rail: China plans to build and expand rail networks in Brazil, Peru and Colombia, though it has run into opposition from environmentalists…

Bottom line? China isn’t looking at this activity as charity. They’re calculatedly seeing these projects in terms of economic return (in hydropower for China, sources of raw materials, new markets for Chinese goods and services, etc.) employment for Chinese abroad, and international sympathy for Chinese ideas and purposes down the road when push comes to shove. And they’re experimenting domestically with vigor: building high-speed trains, high-voltage DC electrical grids, developing capacity to manufacture solar panels, copying cyber technology, etc. They making mistakes and taking missteps along the way, but learning fast in the process – and using that hard-won experience to build preeminence abroad

Call me chauvinist, but it feels like the Chinese are eating from our rice bowl – in plain view. And we’re squabbling with each other while watching them do it.

What to do? We can’t just whine. And we shouldn’t simply go head to head on these terms. We can and should do better. More on that in a future post.

Eye opening article regarding the rise of China compared to the direction of the US.Thanks.

Thanks, Joe!

Bill:-

Lot of meat on this bone. I’ll probably have more to say, but I’d like to take this comment into a particular direction. Let me encapsulate one of the great challenges – almost always unrecognized – we face in a simple question: How do we help our future remember its past? This was sparked by a talk I heard last week by a “resilience planner” from Miami Beach. They are making huge investments in their infrastructure in response to sea level rise. Many of these significantly change how they have done business in the past. But roads, sea walls, buildings all have finite lifetimes. It is almost a certainty that the future the city envisions is not the one it will face when these must be replaced. Simple matters – on what media do we put the records and hope that they will be accessible 30-50 years from now? How do we ensure that the future knows the records themselves exist, and where? Having been involved in infrastructure projects that required finding pipes laid in the ’40s and ’50s, the “as-builts” were far from adequate.

But there is a larger issue you allude to – how do we provide the context so that the records of the decisions made can be understood? We are seeing a wave of the self-righteous trying to wash away memories of our less than pure ancestors. Expunge Calhoun from Yale? I can buy that given that his name was only accorded that honor in the ’30s, and his brilliance was surpassed by the darkness of the causes he championed. But Jefferson and Madison and Woodrow Wilson? I recognize their ties to slavery or segregation; but in the context of their times they were doing the best they could and certainly were bridges to our present. How they made the decisions they made trying to modulate the peer pressure of their times with the voices of their better angels should help us to do the same. We cannot understand decisions made without understanding their context; and that context can help us to make better decisions in the future. But how do we help the future to remember its past?